Reviewing RSPCA's Taking the Lead

A Scientific Analysis of an RSPCA Report

from a group of scientists for evidence-based policy

Executive Summary

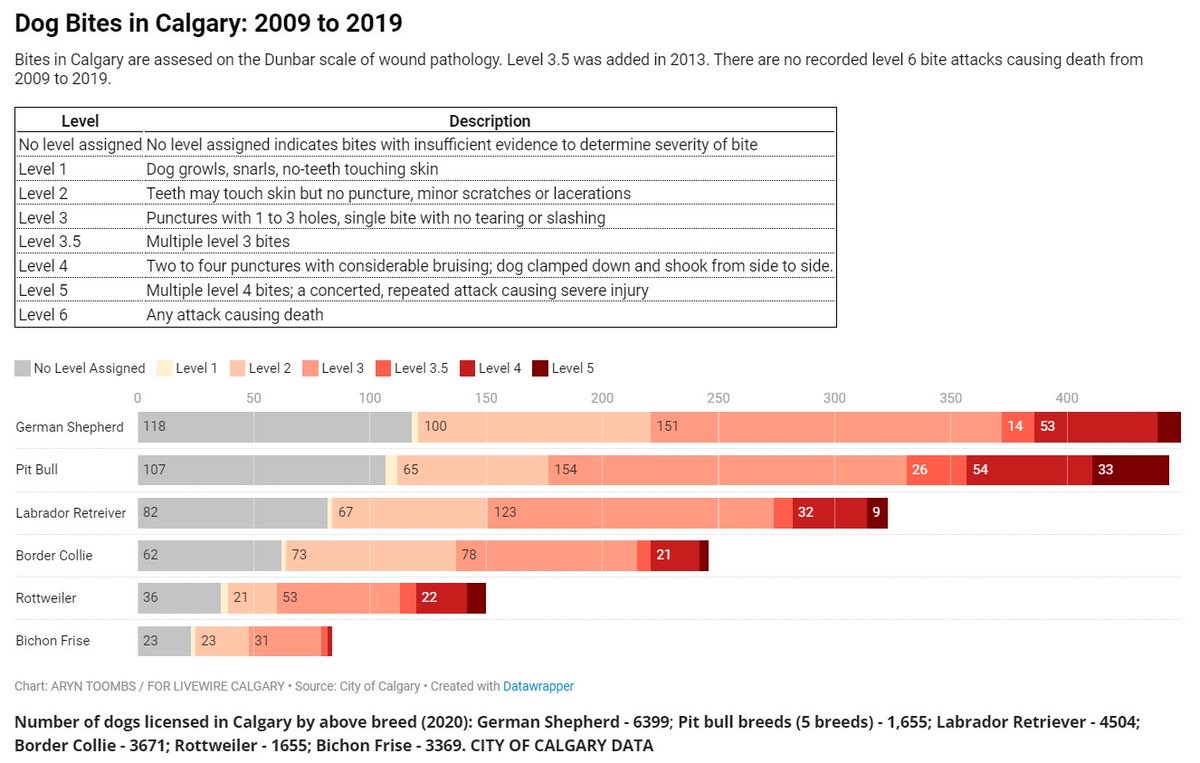

This analysis reveals significant methodological flaws in the RSPCA's 2024 report, Taking the Lead, that undermine its scientific credibility. Our review found the RSPCA selectively cites research that supports their position while ignoring contradictory evidence, particularly regarding breed-specific attack patterns. Their reliance on sources with financial conflicts of interest and methodologically flawed analyses that obscure breed-specific data produces misleading conclusions. In contrast, objective data from Calgary, which the RSPCA presents as a model, shows the average registered pit bull causes 3.8 times more incidents than the average German Shepherd. This report demonstrates why breed-specific legislation remains a necessary component of comprehensive dog-bite prevention policy based on empirical evidence rather than advocacy, addressing a serious public safety issue with significant healthcare implications.

The RSPCA's reports on Breed Specific Legislation (BSL) consistently rely on research that aligns with their stance while disregarding the broader body of medical, veterinary, and epidemiological evidence. This larger body of research overwhelmingly supports the conclusion that certain breeds pose a greater risk and that regulations are necessary to protect both people and pets.

Despite substantial public support and significant scientific evidence supporting restrictions on breeds associated with severe attacks, organizations such as the RSPCA continue to advocate against BSL policies. This position appears to overlook both epidemiological evidence documenting breed-specific risk patterns and the perspectives of victims affected by serious dog attacks.

Report Analysis

The following section headings directly correspond to RSPCA's original section titles[1]. For clarity, these sections are prefixed with "RSPCA Report".

RSPCA Report: Foreword

Despite the many successes in breeding certain behaviours into dogs, such as pointing, herding or retrieving, this foreword implies that dog aggression cannot be reliably predicted via breed, and therefore targeted regulations of breeds bred with the intention of causing harm to other animals, such as fighting dogs, is not possible. The "complexity" of aggression is used to imply that it cannot be regulated, despite the over-representation of a small fraction of dogs in the most serious attacks resulting in fatalities, as assessed by police reports and confirmed by UK courts[2].

RSPCA Report: Acknowledgements

The acknowledgments section credits Dr. Jennifer Maher, a Criminologist and longtime opponent of BSL[3]. Her 2022 report extensively cites publications from the National Canine Research Council (NCRC), an organization founded and funded by Jane Berkey, owner of US pit bull advocacy organization Animal Farm Foundation. This circular citation pattern—where the RSPCA cites Maher, who cites NCRC, which was founded specifically to oppose BSL—reveals a concerning echo chamber of citations rather than objective analysis of the full scientific literature.

RSPCA Report: Executive Summary

This portion of the review, as it is a simple summary of the remaining sections, will be brief.

The report notes that breed bans are "widely condemned by veterinary and animal welfare organisations", yet fails to note both PETA[4] and Protect our Pets[5], a UK group for dog owners who have had their pets attacked by other dogs, support BSL. Instead of a systematic review of the scientific evidence behind why BSL would be required to reduce the frequency of serious dog attacks, the review chooses to characterise current policies in several jurisdictions around the world, implying that the UK should follow their examples, whether or not they are effective in reducing the most serious attacks.

Similarly to other industries looking to avoid regulation[6], the theme of personal responsibility is used to imply that if owners simply tried harder or were more educated, attacks could be reduced. Unfortunately, most evidence used to support the argument that education can be used in this way lacks measurements of reduced "bites" or attacks.[7],[8],[9],[10] This is in direct contradiction to recent statements by the RSPCA that "many people don't think that their dog will bite, and so effective behavior change can be difficult. As well as this, evidence is now showing us that education is often the least effective means of tackling a problem"[11].

This section has some good parts, such as a demand for increased monitoring of dog bite incidents and increased enforcement via Dog Legislation Officers (DLOs). Unfortunately, this section lacks any specific recommendations of how this should be implemented or funded.

RSPCA Report: 1 Introduction and Aims

This section reviews the dire need for dog control, especially with the increase of fatal attacks through 2023. Instead of arguing whether the law works, the report focuses on the law being too "complex" and "confusing", citing a government report summarising opinions from other organizations opposed to breed specific legislation such as Battersea Dogs & Cats Home[12] instead of scientific publications. Also cited is a non-peer reviewed government-commissioned report from Criminologist Angus Nurse[13] which referenced mass-market publications[14] authored by the Director of Science and Behavior for the National Canine Research Council, a subsidiary of US pit bull-focused charity Animal Farm Foundation[15], to downplay the severity of the issue, arguing that "the majority of dog bites caused no actual injury". The Director of Science and Behavior of the NCRC is a longtime pit bull advocate and holds a B.A. in Philosophy and a Masters in English[16].

To argue there is a lack of robust scientific base to support BSL for reducing bites, this publication cites two publications under reference [11]: One study, funded by organizations that oppose BSL (Blue Cross, Dogs Trust, The Kennel Club and RSPCA), analyzed data grouped by broad breed categories rather than individual breeds, obscuring breed-specific attack patterns by combining dogs of vastly different sizes and characteristics while failing to report any specific data for the banned breeds that are actually subject to UK legislation[17]. The second argued there was no difference between "legislated" and "non-legislated" breeds, yet none of the dogs in the "legislated" group are those included in the UK DDA legislation[18]. One cannot dismiss breed-specific problems without breed-specific data.

To argue that legislation alone can make certain dogs more dangerous, in contradiction to the study cited earlier in the paragraph that compared "legislated" to "non-legislated" dogs and found no difference, they cite a non-peer-reviewed report that speculates this effect exists but does not provide any comparison between attack rates for banned dogs before and after legislation is enacted[19].

Further confusing the issue, they present an argument from their own dangerous dogs campaign lead that kenneling banned types poorly impacts dog welfare[20], despite the RSPCA's practice of kenneling for dogs waiting for adoption, at times exceeding years[21].

Lastly, they argue that the prohibition on rehoming requires the destruction of dogs, whereas the long-term kenneling they provide for other breeds prior to rehoming suggests there may be alternative approaches to managing dogs affected by BSL.

The report hints that the pandemic was a contributing factor to dog control issues by linking to a report based on a PDSA owner survey, yet that report has no mention of an increase in bites compared to prior to the pandemic[22]. Peer-reviewed data shows that while lockdowns caused a brief increase in reported dog bites, likely due to exposure effects (being around dogs at home more), these numbers returned to normal by September 2020[23]. If lockdowns were responsible for severe, lifetime behavioural effects, it is unclear why the number of reported bites would increase, then return to normal, then cause a delayed spike in UK fatalities from a small subset of dog types, despite the overall number of reported dog bites persisting at a normal rate.

Instead of accepting that the increase in dog bite-related fatalities may be due to the increasing popularity of pit bull-related American Bullies, the report links to a Defra blog[24] featuring a fact sheet[25] with quotes from the RSPCA's secretariat for anti-breed specific legislation[26], who implies that young children are responsible for their bites by not recognizing "dog body language", and a Dogs Trust employee who also blames children for not yet "understanding [their] dog's communication"[27]. Whilst this is a noble goal, it is unlikely to prevent the most severe attacks, in which even adults who were experts with dogs succumbed to attacks from these dogs[28],[29].

Instead of citing peer-reviewed and independently-funded research, the next several paragraphs circularly reference the RSPCA's own slogans of "deed not breed" via their own membership in various governmental dog control working groups. They then introduce their own commissioned report from Dr. Jennifer Maher.

RSPCA Report: 2 How was the research conducted?

Instead of focusing on effectiveness of dog control policies, the RSPCA decides to instead describe legislation elsewhere, regardless of its effectiveness. It focuses intensely on "The Calgary Model", a model popular with pit bull owners due to its rejection of breed-specific regulations, and its creation by Bill Bruce, affiliate of pit bull advocacy group, the National Canine Research Council[30].

RSPCA Report: 3 Dog control regulation in the UK

This section provides an accurate summary of the Dangerous Dogs Act, which under Section 1 bans five breeds/types: the American Pit Bull Terrier, Japanese Tosa, Dogo Argentino, Fila Brasileiro, and American Bully XL[31]

RSPCA Report: 4 Dog control regulation outside of the UK

As the report notes, there is some variance in which dogs are restricted or banned across different countries, yet all of these locations include the American Pit Bull Terrier. The RSPCA argues that because some breeds, such as the Dogo Argentino, are banned in certain places but not others, this proves that breed-specific laws are arbitrary. However, this ignores the fact that different countries have different thresholds for risk tolerance. By this logic, one could argue that speed limits are flawed simply because they vary between countries, yet few dispute that they play a role in driver safety.

RSPCA Report: 5 Mini case studies on dog control: Ireland, Australia, Canada, USA and Austria

This section features an analysis of several locations worldwide, but once again, the focus is on copycat measures rather than evaluating scientific evidence of what actually works. It also bizarrely frames basic responsible ownership measures such as leash laws and spay/neuter requirements as if they were punitive restrictions placed on the dog rather than reasonable expectations of the owner.

Notably, this contradicts their argument in section 4 that the variance in breed bans between countries shows that bans are arbitrary. In contrast, this section argues that differences in non-breed-specific restrictions shows the flexibility of alternative approaches. If legal inconsistencies are considered a flaw in one context, they cannot simultaneously be presented as a strength in another without a clear justification.

RSPCA Report: 6 Exploring the Calgary approach to responsible dog ownership and dog bites

The Calgary approach, frequently known as "The Calgary Model", is often proposed by proponents of removing pit bull breed bans[32]. It is argued that this legislation, funded by licensing, can reduce the amount of serious attacks via responsible ownership.

This section stresses the high licensing rates in Calgary, achieved through incentives, monitoring and social peer pressure. This section appears to blame other factors for attacks, and whilst it presents a breakdown of number of licenses for each breed registered, it does not report any attack data by breed, making it impossible to know from the data they chose to cite whether breed is or is not a factor. Instead, they use the same strategy as used in the RSPCA-funded publication cited in section 1 Introduction and Aims, which reported bites by breed family, obscuring individual breed data[33]. Fortunately, other publications have reviewed the breakdown of Calgary dog attack data by breed, providing an illustration that despite the Calgary licensing system, certain breeds cause more attacks, and certain breeds cause more damage than others[34], as supported by the wider scientific literature.[35],[36],[37],[38],[39].

With Calgary data broken down by individual breeds, we see that when adjusted for number of registered dogs per breed, Pit Bulls on average cause 3.8 times as many incidents as German Shepherds and 3.7 times as many incidents as Labrador Retrievers, and that Pit Bulls cause more attacks at Dunbar Level 3 and above than any other breed. These severe attacks result in disproportionate healthcare costs through emergency services, reconstructive surgeries, and long-term rehabilitation.

The evidence clearly shows whilst breed-neutral policies have their place, the continued allowance of ownership of dogs originally bred for fighting, such as Pit Bull-type dogs[40], ensures a disproportionate amount of attacks from these subgroups of dogs, even in locations with strong licensing programmes such as Calgary.

In 2022, Betty Ann Williams was attacked and killed by 3 pit bulls in Calgary that had escaped from their owner's yard. The owner was fined $18,000[41], but no criminal charges were made[42].

These attacks not only represent personal tragedies but impose substantial preventable costs on healthcare systems and resources.

RSPCA Report: 7 Lessons learnt from other countries for reducing dog bites in the UK

The publication emphasizes personal responsibility and education over regulation, a strategy that has been critically examined in other public health contexts[44]. Similarly to its earlier mention of education in section 1 Introduction and Aims, it fails to provide any studies that link education programmes to measurements of reduced bite incidents.

The section focuses on other partnerships such as the Merseyside Dog Safety Partnership, which was created in 2015, and is includes several partners that propose all strategies except for breed restrictions, including Dogs Trust and PDSA[45]. Despite this partnership, NHS figures from 2022 show Merseyside having ten times more attacks than other locations in the country[46].

RSPCA Report: 8 Achieving effective dog control in the UK

What we see in the RSPCA's report is a summary of evidence that fails to meet high scientific standards, by relying on self-funded studies, owner surveys instead of measurements of bite incidents, and numerical techniques that combine vastly different dogs into breed groups. To close out, it prominently features the Calgary licensing scheme without its full context that illustrates that despite a robust licensing scheme, a system without bans for the most dangerous of dogs will lead to disproportionate attacks from those types of dogs.

Conclusion: The Need for Evidence-Based Policy

The RSPCA fails to present a balanced assessment of the evidence surrounding breed-specific legislation, instead relying on self-referential citations and advocacy-oriented research. The report selectively ignores critical data showing clear breed-specific patterns in serious attacks, particularly from the Calgary model. By obscuring individual breed data and focusing on other strategies without acknowledging their limitations in preventing severe attacks from high-risk breeds, the RSPCA's recommendations ultimately prioritize advocacy over public safety. A truly evidence-based approach must integrate the full spectrum of veterinary, medical, and epidemiological research to build policies that effectively protect both the public and responsible dog owners.

Recommendations

Based on this analysis, we recommend

1. Maintain BSL Protections

The UK should maintain the existing provisions of the Dangerous Dogs Act covering pit bull-type dogs, Japanese Tosa, Dogo Argentino, Fila Brasileiro, and American Bully XL breeds given their documented higher risk of severe attacks.

2. Enhance Data Collection, Including Breed

Implement standardised reporting of dog bite incidents including breed identification, attack severity using the Dunbar scale, and context. Analyses based on combining radically different dogs by breed groups is unhelpful. Decisions about breed-specific problems need to be addressed with breed-specific data.

3. Conduct Cost-Benefit Analysis

Evaluate the public health, personal health and NHS resource costs of severe dog attacks against the restrictions on a small subset of high-risk breeds to inform proportionate and cost-effective policy responses.

4. Require Independent Review

Future policy reviews should require disclosure of financial conflicts of interest and ensure citation of the full spectrum of medical and epidemiological literature, not just advocacy-oriented research.

5. Implement Complementary Measures

While maintaining BSL, implement evidence-based complementary measures including enhanced enforcement and stronger penalties for irresponsible ownership practices.